LAUREN GEIGER & JASON VELDER

While environmental protection has gained significant attention in recent years, it has been a subject of international concern for over five decades. In the aftermath of World War II, the United Nations took steps to formulate policies and treaties aimed at safeguarding the environment and preventing both environmental and humanitarian crises. Aligned with its overarching mission of upholding global peace and security, the United Nations introduced the Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD). This treaty, which came into effect in 1978 as per Article IX(3), was designed to curb practices that could harm the environment. Despite its continued relevance, ENMOD’s efficacy remains limited due to a lack of robustness and specificity.

This treaty, despite its flaws, does go hand-in-hand with major UN goals, specifically those related to international peace security, and human rights. The countries that are parties to ENMOD essentially pledge not to use (in a “hostile” manner) or aid in the use of “environmental modification techniques,” which can be defined as “any technique for changing – through the deliberate manipulation of natural processes – the dynamics, composition or structure of the earth, including its biota, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere, or of outer space” . Biowarfare (ex. genetic engineering) and intentional flooding through the destruction of a state’s dams are some examples of “environmental modification techniques.” In addition to those tactics used in both the First and Second World Wars, the world was particularly concerned by the actions of the United States in the Vietnam War, which ultimately prompted the formation of this treaty. In essence, this treaty aims to prevent a relatively new means of warfare from becoming the “norm,” and thus push states to consider the environmental and human impacts that war can ultimately have on a state and the world more broadly.

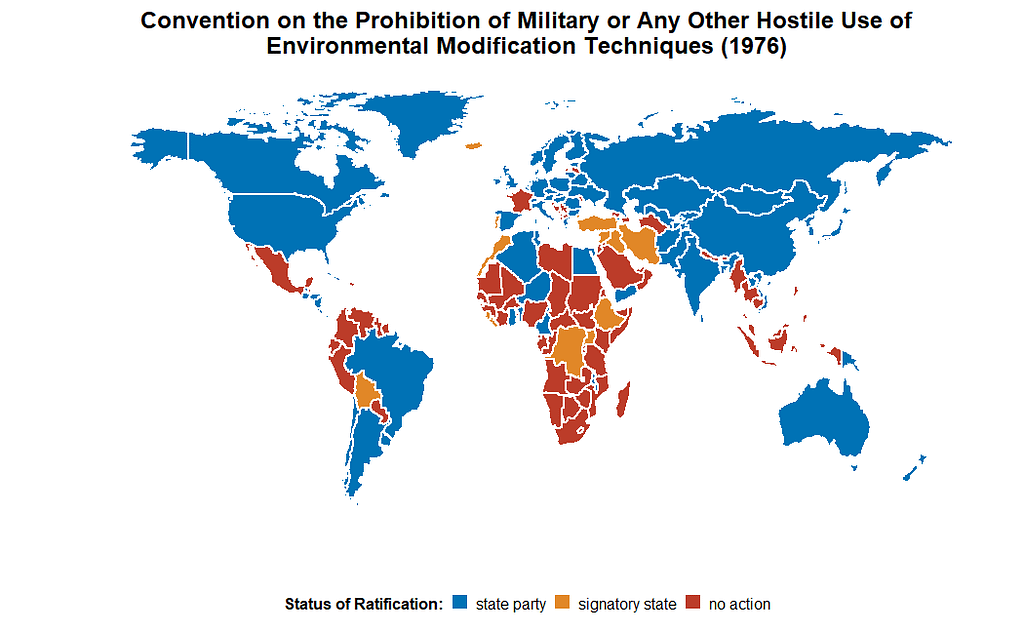

Many states recognized the aims and importance of ENMOD and have since either signed or ratified the treaty in years spanning from 1978 to 2015. The map depicted below illustrates each state’s current status concerning the treaty and classifies them as having signed, but not ratified (i.e., signatory state), ratified (i.e., state party), or taken no action concerning ENMOD.

Except for France, all members of the Security Council’s permanent members are state parties of this treaty. Most of the states that decided to engage with the treaty have ratified it, but a small percentage have only chosen to become signatory states, including Luxembourg and Bolivia. Although there is widespread support for ENMOD, there is still a significant portion of states, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia, that have yet to either sign or ratify the instrument.

ENMOD’s provisions impede significant change within the international community regarding environmental warfare. For instance, while it outlaws the use of environmental modification techniques linked to hostile intent, it lacks clarity on defining what constitutes “hostile” intent. Focusing primarily on tactics, ENMOD fails to include a clause prohibiting states from developing these techniques. Overall, the lack of specificity prevents ENMOD from becoming a substantial force in international law.

Owing to its lack of precision, ENMOD falls short of garnering enough support to prohibit and eradicate environmental modification techniques. As technology advances, these tactics become more accessible and achievable — a concerning prospect highlighted in the convention’s opening statements (Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques 2). Although flawed, the convention is still an important legal instrument. When aligned with the objectives of the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, the ENMOD can serve as a crucial foundation for the eventual eradication of some of the environmental damages associated with warfare.

Want to learn more about this legal instrument?

Data on this convention’s ratification status is available on the World Politics Data Lab’s GitHub page. The most recent dataset was uploaded to the repository on October 1, 2023.

For more information on the convention’s history and its current application, please refer to the following academic writings:

Bouvier, A. (1991) “Protection of the natural environment in time of armed conflict,” International Review of the Red Cross (1961 – 1997), Cambridge University Press, 31(285), pp. 567–578.

Juda, L. (1978) “Negotiating a treaty on environmental modification warfare: the convention on environmental warfare and its impact upon arms control negotiations,” International Organization, Cambridge University Press, 32(4), pp. 975–991.

About the authors:

Lauren Geiger is a senior, double majoring in Political Science and French at Drew University.

Jason Velder is a junior, with a major in International Relations and a minor in French at Drew University.

Editor’s note: This post is part of a long-term project. Students enrolled in Drew University’s Semester on the United Nations, Principles in International Law and International Human Rights have been and will be collecting data on the ratification status of treaties deposited in the United Nations Treaty Collection. For more information on this project and its learning goals, click here.